EMILY WHANG / NEXTGENRADIO

home?

Owen Racer speaks with Lora Ann Chaisson, a tribal leader in Southeast Louisiana. Residing in Pointe-aux-Chênes, near Isle De Jean Charles, Chaisson is the Principal Chief of the United Houma Nation. The Indigenous tribe of nearly 19,000 embodies Chaisson’s feelings of home: family, food, and the Bayou.

Family and food are central to Houma tribal chief’s sense of home

Listen to the audio story

Click here for audio transcript

Lora Ann Chaisson: Home is where the family’s at and food and the water and land.

My name is Lora Ann Chaisson. I have the responsibility of taking care of 19,000 citizens.

I live in a community called Bayou Pointe-aux-Chênes which means “point of the oaks.”

It’s different from the city of New Orleans. I mean, even though we’re right next to each other, we only an hour and a half away from each other, it’s a whole different world.

The word bayou is — it’s a natural waterway.

It’s like your hand, like the palm of your hand, and each finger is a bayou. Because of forced migration from European encroachment, we have migrated to the bayou areas.

The bayou is just different. Everybody knows everybody. And if you need something, you can just make a phone call, and say, “Look, I need you to come get this alligator out my yard [laughs].”

Family is the most important thing for me. I’m one of 31 grandkids. My dad has a 102 first cousins. So family is home.

I grew up fishing, you know, and shrimping all my life. I remember my grandfather and my dad and my sister and I — we went out shrimping with my grandfather and my dad. It was a day off from school. And we caught so much shrimp that we could hardly keep up. The boat was low and we was just like put-putting [laughs]. I’ll never forget that. It was loaded down with shrimp. I mean, shrimp was at our feet, you know. And my dad is like, “Y’all smashing the shrimp! Ya’ll gotta get up, put it in your shoes, somethin’! But don’t step on it!” [laughs]

Food always bring our tribal community together. You come to our home, we’re going to feed you.

The word “gumbo” is from Africa. Our people still do a traditional dish, and you will never find that in any restaurant. You have to go to someone’s home to have a traditional gumbo.

We have elders that still harvest sassafras leaves. They dry it, grind it, and then that’s what we use as our thickener. Over here in New Orleans they use a roux, a roux consists of flour and oil. Our thickness is the leaves of a tree.

I bought my house 22 years ago, and my boys were hunting deer in the back of my house. It was all woods 22 years ago. Now they could fish out of the back of my property.

The trauma that happens with hurricanes can really put a toll on you. You could really visibly see it when Hurricane Juan hit. And then we’ve had Andrew, Lilly, Gustaf, Ike, Katrina, Rita. Our oak trees are not growing like they used to any longer because of all that saltwater from the hurricane. The sediment, the soil is different now.

That’s the reason why in my area, we lose a football field every hundred minutes, a football field of land every hundred minutes. Can you imagine that? That’s what’s happening to our area and that’s no new fault of our own.

I really don’t want to leave the bayou, but the flooding, you know, getting older. The insurance keep going up.

I feel like I’m a very strong woman. I’m a single woman, I have one salary. That’s it.

My home is going to be somewhere else … it’s not in our tribal community, but my heart will always be on a bayou.

Before the Gulf of Mexico crept in and overtook the backyards of Southeast Louisiana residents, home for Lora Ann Chaisson meant interconnected bayous, afternoons in the garden and hunting deer with her family in Isle De Jean Charles.

Chaisson is the Principal Chief of the nearly 19,000-member United Houma Nation, one of the state’s recognized tribes of Indigenous people. Her sense of home has become further ingrained in land that’s continually eroding to the rising sea.

This erosion, coupled with the 10 hurricanes over 22 years that Chaisson has endured, is furthering the distance between her physical home and her feeling of home.

But Chaisson’s meaning of home can’t be washed away. It is cemented in ancestral lands and traditions, the “heaven” smell of the bayou, and its catch of the day.

Principal Chief Lora Ann Chaisson frequently finds herself in New Orleans, recently demonstrating traditional basket weaving and visiting the “special” City Park

OWEN RACER / NEXTGENRADIO

“[The bayous are] like your hand, the palm of your hand is Houma, the city named after our tribe and each finger is a bayou, and there’s water that separates each tribal community,” Chaisson said.

Centuries ago, European settlers forced her tribe to migrate down the Mississippi River. Now, Chaisson and her people are having to do the opposite — move inland. Chaisson recently made the difficult decision to put her tribal home in Pointe-aux-Chênes for sale.

She cites her sense of security being stripped over the past few years through various means as another reason for the nearing move. Recently, crime has also arrived at her front door along with the tide. A home robbery and a bullet through her front door happened within a month’s span.

Rising home insurance rates in the bayou — due to increasing hurricane threats and damage — have almost priced Chaisson out of her hurricane-weathered home, where her living room stands 11 feet in the air.

Unfortunately, this isn’t Chaisson’s first experience with displacement. Her father, Theo Chaisson, had to relocate to the city of Houma from Isle De Jean Charles because of the volatile climate. Soon, both of them will have to travel down to the bayou to breathe the air of their home.

Lora Ann Chaisson making alligator jewelry for the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival as her father, Theo (right) watches on from his marina in Isle De Jean Charles. April 26, 2023.

OWEN RACER / NEXTGENRADIO

Chaisson’s rather extensive family has longtime close ties to each other. The natural environment, culture and food are of utmost importance to them. From “the three sisters” dish of corn, beans, and squash, to shrimp gumbo, the cultural roots are ever-present on the table. In the bayou, food is one of the binding commonalities.

The rising waters encroaching Chaisson’s bayou community aren’t all grim. More water means more area in which to fish. Although the water can provide a steady stream of anxiety, it used to provide designated shrimping days off from school for Chaisson as a kid.

When shrimp season opened on May 1 and Chaisson was caught in New Orleans, she regretted not being in the bayou for the day of tribal significance.

“My friends, some of them call me a shrimp snob,” Chaisson said. “I’m a seafood snob.”

Despite the resilience required to live in and near Isle De Jean Charles, she still recalls the joyful rides with her sister and father in a boat weighed down by a day’s catch of shrimp.

“We caught so much shrimp that we can hardly keep up, the boat was low,” Chaisson said. “It was loaded down with shrimp, I mean shrimp was at our feet.”

When Chaisson isn’t voicing activism on behalf of her tribe, she’s frequently found gathering community members around a meal.

“Food always brings our tribal community together,” Chaisson said. “You come to our home, we’re going to feed you.”

On a recent sunny afternoon in Isle De Jean Charles, atop her father’s marina deck, Chaisson’s guests enjoyed her fried fish and cooked turtle while she pieced together her alligator jewelry.

Proudly waving Houma’s red crawfish tribal flag, Theo’s Isle De Jean Charles marina has evolved into a communal waterfront gathering ground.

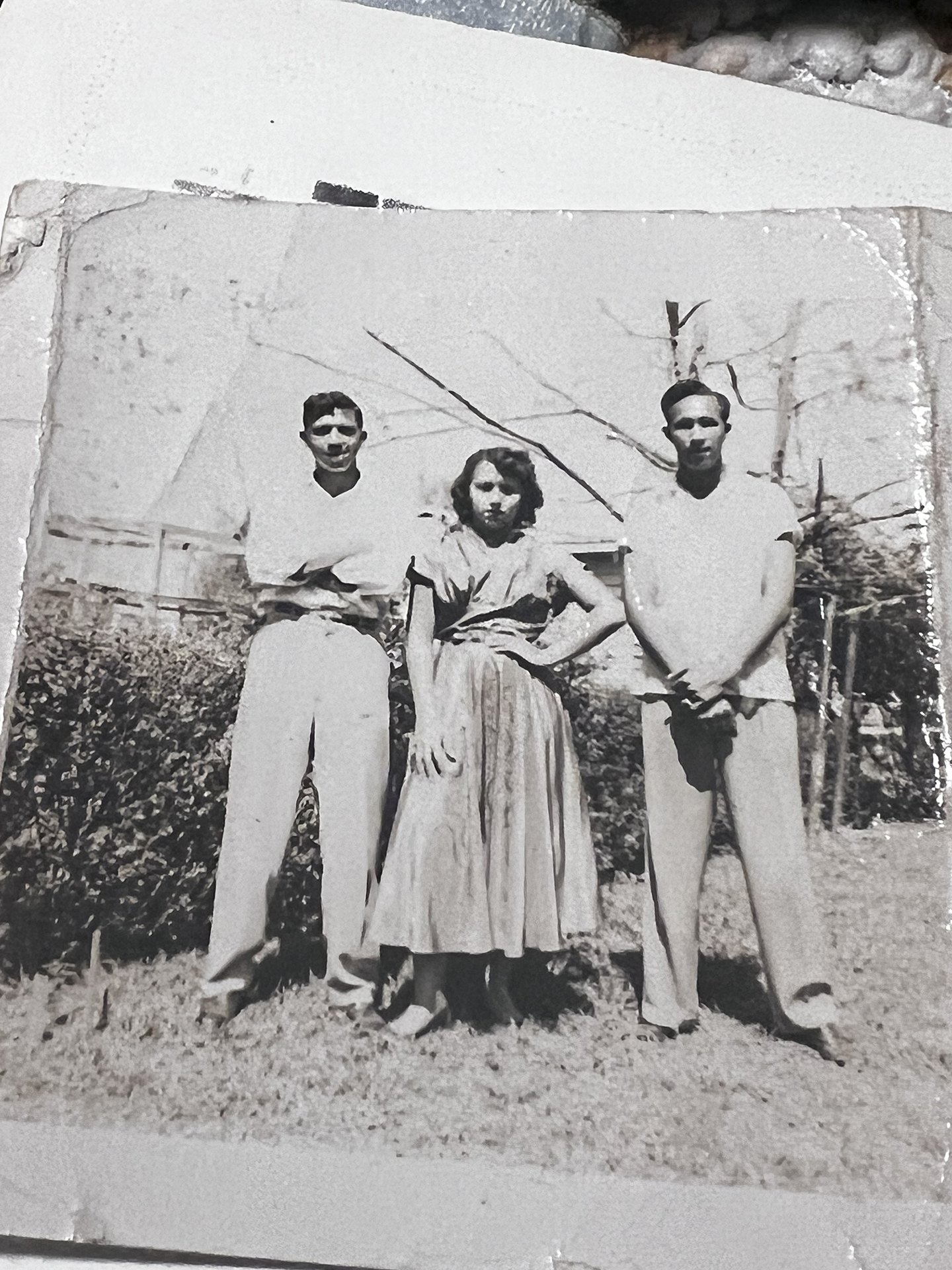

Lora Ann Chaisson’s mother (center) who is from neighboring Dulac, La., and her relatives.

COURTESY OF LORA ANN CHAISSON

A self-described “shrimp snob,” Lora Ann Chaisson knows good shrimp when she sees it, and even when she smells it.

COURTESY OF LORA ANN CHAISSON

A like-minded feeling of home lives nearby: New Orleans, where Chasisson feels blessed to frequently visit. The city’s famous City Park was once the United Houma Nation’s hunting grounds. Now, city-goers bike, run, and bask along the park’s waterways.

“Even though we’re right next to each other — we only an hour and a half away from each other — it’s a whole different world,” Chaisson said, comparing New Orleans to her home in the bayou. “The bayou is just different, everybody knows everybody.”

Not only does hunting no longer take place in City Park, it no longer does on her father’s land in Isle De Jean Charles. The land is now a rising waterway. Where her father, Theo, once owned a house now stands the marina, where he charges $9 per boat launch, something the local shrimping community utilizes.

Spanish moss, which Lora Ann Chaisson holds above, and palmetto trees were utilized in their tribal communities for bedding and houses, respectively. May 1, 2023.

OWEN RACER / NEXTGENRADIO

Even though we’re right next to each other — we only an hour and a half away from each other — it’s a whole different world. The bayou is just different, everybody knows everybody.

“In my area, we lose a football field of land every 100 minutes,” Chaisson said. “Can you imagine that? But that’s what’s happening to our area and that’s no new fault of our own.”

Chaisson does not want to leave the bayou, but with her tribal community house for sale, a safer future inland looms for the principal chief, one outside the tribal territory. However, wherever she may relocate, Chaisson’s home will always be here with family.

“My heart will always be on a bayou,” she said.